This report analyses and evaluates why a highly successful company like Kodak ran out of money and had to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2012.

Clayton Christensen’s theory of ‘sustaining and disruptive innovation’ in consideration with several other frameworks has been applied to Kodak’s case to evaluate the leadership and management of innovation and change at Kodak from 1975 onwards.

This report is based on the popular Harvard Business School case study of Kodak and The Digital Revolution by Giovanni M. Gavetti, Rebecca Henderson and Simona Giorgi, published in November 2004 and revised in November 2005.

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Brief Profile of Kodak in 1975

1975 was an important year in the timeline of the Eastman Kodak Company. The company invented the Digital Camera, one of the greatest technological inventions of the modern world (Castella, 2012) and yet the greatest irony; the same digital camera was starting point of Kodak’s slow demise.

Founded in 1880, Kodak was one of the most innovative companies in most of the 20th century. The company built on a culture of innovation and change (Kotter, 2012), transformed photography from a complex activity into an everyday life activity accessible to billions of people (Munir and Phillips, 2005) and thus revolutionised the entire photography industry.

By selling its camera for a low price and using the razor-blade strategy to drive profit from selling consumables such as films, Kodak achieved higher profits and continuous growth (Gavetti et al., 2005).

The invention of the digital camera in 1975 by Steve Sasson, one of Kodak’s engineers was part of intensive investments in research and development and portrays how innovative the company was back then. Kodak, however, didn’t see the potential in the digital camera early and couldn’t capitalise on the invention. As films were bringing in most of the profits, investing in the digital camera would be cannibalising their own profits.

Kodak accounted for 90% of film and 85% of camera sales in the US by 1976 (Gavetti et al., 2005). A company employing more than 100,000 people to sell film rolls to generate billions in revenue then, couldn’t care much for a filmless device that could potentially be a threat to their own business.

Kodak held back from developing digital cameras for the consumer market for fear of killing its profitable film business (Usborne, 2012). The company brought its first digital product in the market in 1991, and although, there were few players in the market already, Kodak was initially successful in the Digital market.

Until 1999, Kodak had a share of 27% in the US digital market, but despite the market share and position, Kodak was losing $60 for every camera it sold in 2001. Kodak was used to earning really high-profit margins on its films, and in comparison, the margins in the consumer electronics hardware market were much smaller (Gross, 2012).

Eventually, Kodak executives’ mindset of razor-blade strategy forced them to focus on other consumables rather than the electronic device itself.

So, how could an innovative and massively successful company like Kodak which dominated photography all of the 20th century (Harris, 2014) had to give up on the modern digital revolution that it had helped start in 1975?

2.0 Sustaining and Disruptive Innovation at Kodak

Photography giant Kodak was undoubtedly an innovative company that made photography accessible and affordable to the general mass. The fact that a company dies because they do not respond to the disruptive changes in its marketplace just doesn’t apply to Kodak (Anthony, 2012).

How could a company that invented the digital camera, invested heavily in digital imaging and bought websites like photo-sharing site Ofoto, be liable to succumb to a digital revolution?

Perhaps, it was a different challenge for Kodak and as cited by The Economist (2012) Clayton Christensen, believes that the problem was fundamental and Kodak faced an enormous challenge with a significant shift that couldn’t be met with existing technology.

Indeed Kodak saw a massive transformation in the industry, first with digital cameras and second with camera-enabled smartphones. To analyse what happened with Kodak with change and innovation let’s use Clayton Christensen’s theory of ‘sustaining and disruptive innovation’ as a framework for our further analysis.

2.1 Christensen’s Theory of Sustaining and Disruptive Innovation

Companies need to innovate with their products and services to be competitive in the marketplace (PwC, 2012). Clayton Christensen’s theory of ‘sustaining and disruptive innovation’ is one of the most popular theories to understand how innovative new entrants beat the long-standing successful companies like Kodak.

Christensen (1997) in his popular book The Innovator’s Dilemma, distinguishes two types of innovation i.e. sustaining, and disruptive innovation. Interestingly, Kodak has been through both types of innovation and couldn’t withstand the disruptive innovation of digital imaging after 1975.

Sustaining Innovation is based on developing current technologies that overall improve the performance of established products being either of radical character or of an incremental nature. In contrast, “disruptive” innovation introduces new products or services that may not be standard as of currently available products but with other dimensions such as simpler, convenient, cheaper and accessible (Christensen, 1997).

Kodak with its introduction of film rolls was “disruptive” as the company made photography much easier and affordable to the masses. Kodak kept on improving their performance of black-and-white film rolls to better films, in colour and of high quality, all of which were sustaining innovation for the company.

The emergence of Digital cameras, similar to film rolls, added a different dimension to photography. It wasn’t about competing on quality anymore. People back then adopted digital for entirely different reasons other than quality.

Thus, the innovator’s dilemma for companies like Kodak is whether to focus on current customers or to focus on a new population of consumers with lower-margin opportunities.

In hindsight, it seems Christensen’s claim of established companies face difficulties dealing with disruptive technology has come true with Kodak. But was “disruptive innovation”, the reason behind the failure of Kodak?

The detailed look at sustaining and disruptive innovation of Kodak based on Clayton’s framework under separate headings below might help us answer that.

2.2 Competition and sustaining innovation in the film business

2.2.1 Sustaining Innovation in Digital Technologies

Successful firms like Kodak, according to Christensen, are most effective at implementing and developing incremental or sustaining innovation (Dodgson et al., 2013). This can be related to the failure of Kodak to commercialise disruptive innovation like digital imaging as the company was mostly concerned about its current customers’ defined and predicted needs back then.

Christensen himself discussed how Kodak, in 1999, tried forcing its digital photography to compete on “Sustaining Innovation” basis against film and other consumer electronic players such as Sony and Canon (Christensen, 2006). Kodak offering a simple, convenient and low-priced camera called EasyShare is one example of Kodak’s sustaining innovation strategy to focus on digital imaging.

2.2.2 Sustaining Innovation in Film Era

Before digital, the continuous improvement in the quality of films for Kodak can be taken as sustaining innovation. Kodak had a huge share of the film market and literally didn’t have any competition for a long time. When Fuji emerged as a firm competitor for Kodak in its film business (See image below), Kodak’s management failed to maintain the same value proposition and continuously lost its market share to Fuji.

The market leader of Japan with more than 70% market share around 1984 steadily increased its market share in the US market by offering its products for lower prices than Kodak. The aggressive competition from Fuji also triggered Kodak to carry its sustaining innovation faster.

Kodak’s introduction of disposable cameras, for instance, was only after the success of Fuji in its home market. Kodak’s other significant sustaining innovation included the firm’s move into medical imaging and graphic arts exploiting its core capability in silver-halide technology.

2.3 Response to the disruptive innovation of digital imaging

Christensen’s theory, as discussed earlier argues disruptive technology is usually cheaper, easy and more accessible. Applying this to Kodak, when digital cameras were introduced, they were remarkably expensive (by 1995, only three models were priced under $1,000) but became cheaper and accessible comparatively over time.

Christensen’s theory, however, fails to address the fundamental shift in digital imaging and other factors of digital imaging that made it a disruptive innovation to replace the existing film market.

One of the limitations of the theory is that Christensen’s characteristic of disruptive innovation products fails to explain the digital imaging shift. People adopted digital imaging not because it was cheaper or smaller, but in fact, because it changed the process of photography (Munir, 2012).

People were able to see the image instantly and copy/share it on the Internet, which also impacted the distribution channel Kodak had built over the years and formed an entirely new digital imaging chain (Gavetti et al., 2005).

Christensen’s theory elaborates that disruptive technologies bring to a market a very different set of value proposition than had been available previously. Kodak seriously misinterpreted the value proposition digital imaging brought to the photography industry.

Kodak’s efforts of film-based digital imaging in 1990-1993 such as introducing Photo CD was an effort geared towards creating synergies between film and digital, which shows Kodak hadn’t fully grasped the digital movement until 1993.

Christensen further argues that established companies find it extremely difficult to invest adequate resources in disruptive technologies. Kodak’s comfortable investments in films continued because that’s where all the profits came in.

Christensen’s theory points out that large companies adopt a strategy of waiting until new markets are “large enough to be interesting” and this is in line with Kodak’s strategy back then. Kodak only started investing heavily in digital imaging after the market was filled with several players.

Investment in digital imaging until Fisher’s era was scattered and it was only after Fisher in 1994 that Kodak separated the digital imaging operations that paved the way towards the dedicated digital movement for Kodak.

2.4 Resources, Processes and Values

Christensen et al. (2004) framework of resources, processes and values (RPV) can be applied to Kodak’s case to understand how the firm struggled to deal with digital technology. As for resources, Kodak certainly had enough capabilities to exploit digital technology to its advantage.

New processes were necessary for Kodak to succeed with digital technology and Kodak tried to create those processes, be that by bringing CEOs from different backgrounds or by establishing separate divisions for digital operations. The significant problem lay with values, how could Kodak prioritise digital imaging when it posed a major threat to cannibalise its profitable and attractive film business?

Such situations, according to Christensen, create innovator’s dilemma for companies. The view is also supported by the review of disruptive innovation theory by Yu and Hang (2010) and the primary solution advised in such cases is to establish an autonomous organisation.

Had Kodak established digital imaging as a stand-alone organisation, it would have definitely helped create a different set of processes and values, and this might have helped Kodak’s transition to disruptive technology.

3.0 Kodak’s Leadership and Strategy for Growth and Profits

The leadership at Kodak executed several decisions pertaining to a certain strategy and direction for growth and profits over time.

Considering such Kodak events from the case study ‘Kodak and Digital Revolution’ by Gavetti et al. (2005), strategies adopted by the leadership positions during different times can be analysed and evaluated to explore the management of innovation and change.

3.1 Kodak’s Leadership 1975 – 2012

Looking at the leadership, achievements and transition phases of Kodak, three separate time periods based on the CEOs after 1975 can be considered for this analysis.

The period of 1975 to 1993 included CEOs Walter Fallon (1972 – 1982), Colby Chandler (1983 – 1989), and Kay Whitmore (1990 – 1993) and the interesting observation about this period is that all the CEOs came from the same manufacturing background within Kodak itself.

Another period of 1993 to 2005 included George Fisher (1993 – 2000) and Daniel Carp (2001 – 2005) as CEOs of Kodak. Fisher was the first outsider to run Kodak and while he emerged as the strong leader to push Kodak into the digital age, he considerably failed in changing the culture of Kodak.

Another CEO – Carp’s significant achievement included improving consumer digital imaging by introducing the first digital film processing software for the masses.

The recent period, after 2005 until Kodak filed for Chapter 11-bankruptcy protection in 2012 was headed by Antonio Perez as CEO of the company. Although Kodak’s profit was declining then, Carp was successful in building the digital imaging brand for Kodak being No. 1 in the U.S. market and No. 3 worldwide (Dickinson, 2012).

But as Kodak lost hope and couldn’t sustain with fewer margin profits from Digital cameras, Perez started exploring other options such as restructuring the company and focusing on other service-oriented business models (Hamm and Symonds, 2006).

3.2 Ansoff’s Matrix for Products and Markets

Ansoff (1957) presented a framework that can be used to analyse strategies used by Kodak under different time periods of leadership mentioned above.

Considering the activities of Kodak regarding products and markets (see the figure below for an overview of Kodak’s Ansoff’s Matrix framework), the general theme that can be deduced is that the company mainly focused its efforts on Diversification.

And looking at its competitor Fuji which survived because of extreme diversification, one can argue that Kodak did the very best thing. My analysis, however, suggests there wasn’t adequate diversification and that the process was poorly managed.

Kodak, during the period of 1975 to 1993 started off with an ill-conceived process of unrelated diversification by investing in a pharmaceutical firm, the only logic behind being the industry relatedness with its core chemical business.

The company carried on with its unrelated diversification spree, which then was divested to pay off debts, immediately after Fisher came on board in 1993.

Unlike the previous leadership that believed their core business was chemical, Fisher believed the company was a film and consumer product business. Although divesting the health sciences unit helped to bring Kodak’s core focus to imaging, the previous diversification efforts were all wasted.

In hindsight, Fisher’s decision to divest the health science, just because it didn’t turn high margin profit (like the film business) immediately, cost the company in overall. Fisher initially pursued market penetration strategies by underestimating the digital adoption rate in emerging economies like China.

When the strategy failed, Fisher shifted towards a product development strategy by looking for a network and consumables-based business model.

3.3 Ansoff’s Growth Vector Components

Expanding the framework further, Ansoff’s growth vector components represent two extreme choices;

- Continue serving present markets with existing product/service or technology

- Serve new markets with new product/service or technology

Analysing those growth components, it’s clear that Kodak was more focused on serving present markets with its existing products and technology.

Unlike Kodak’s focus, disruptive innovation centres on creating new sets of markets and customers (Dodgson et al., 2013) and thus the framework makes it distinct why Kodak failed at disruptive innovation.

3.4 Growth Strategy of Kodak – BCG Matrix

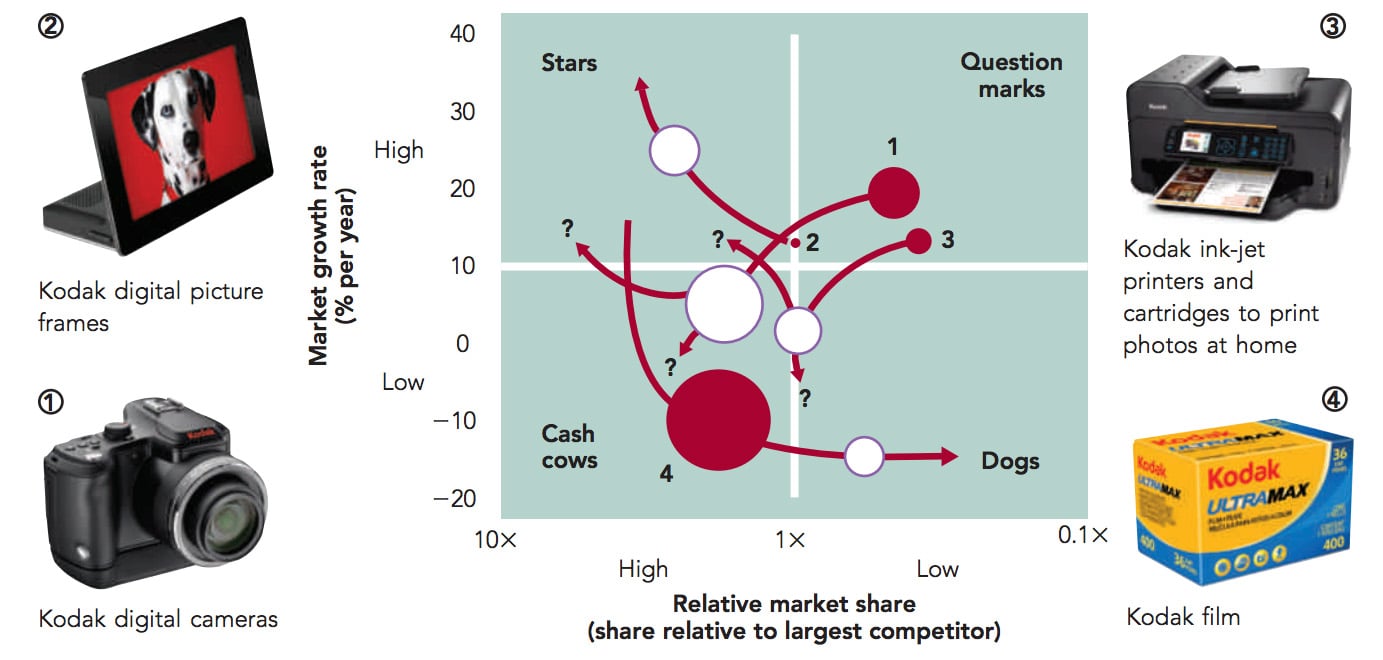

Application of another similar framework Boston Consulting Group (BCG) matrix to identify growth targets for Kodak during the emergence of digital cameras is portrayed in the image below where Digital cameras are ‘question marks’ and films are ‘cash cows’ for the company.

The application of the matrix suggests business units like the digital camera should be injected with huge cash to maintain their market share. This also explains Kodak’s management dilemma of choosing to invest in the right ones and divest the others.

4.0 Culture and Climate of Kodak

As an extension to Christensen’s theory of disruptive technologies, Lucas and Goh (2009) propose a framework that includes considerations of organisational change, and the culture of the organisation to evaluate how firms deal with disruptive technology.

The framework illustrates that Kodak had developed a robust culture over time but the previously successful culture didn’t work with the rapidly changing environment and rather became a barrier to the company’s digital innovation.

4.1 Culture Change and its Effect on Decision Making

Overall, Kodak had similar culture over time, and when leaders outside of Kodak’s background (especially Fisher) tried changing it, they faced several difficulties.

Unlike other CEOs, Fisher was brought into Kodak from outside of the company with the challenging responsibility of taking Kodak to the digital age. Fisher tried restructuring Kodak and creating a separate digital division but this didn’t help to change the culture of Kodak.

Noticeably, middle managers resisted the change and alignment with the previous culture, and they didn’t act in bringing the ideas from lower levels of the organisation.

Kodak was a bureaucratic organisation with a tall and hierarchical structure that had a different culture of information passing from top to bottom, and this didn’t help leaders like Fisher that wanted to change the dominant culture.

4.2 Lewin’s Force Field Analysis

Kodak’s inability to change can be evaluated using a framework of Lewin’s force field analysis that helps analyse forces for and against change in Kodak’s digital transition. The Figure below shows forces that were mainly dominant in Kodak’s move to digital.

Lewin’s Force Field Analysis for Kodak – For and Against Kodak’s Digital Change

Forces For Change

- Growing Consumer Demand

- Leadership of George Fisher

- Research Forecast

Forces Against Change

- Organisation Structure (Tall, Bureaucratic)

- Existing Profitable Film Business

- Kodak’s Culture

- Kodak’s Middle Manager’s Attitude

The change was mainly restrained by factors including Kodak’s structure and culture/climate among others and it became very difficult for Kodak to overcome these restraining forces with its limited driving force.

5.0 Summary of Findings

While on the surface it seems Kodak is another victim of disruptive innovation, this analysis and evaluation of Kodak’s case have found several other problems behind the failure of Kodak’s digital innovation.

A few of such problems realised from the above frameworks include the failure of Kodak to change its culture, the previous success of Kodak in the film industry (that kept Kodak focusing on existing markets with existing products), cognitive inertia, and the compliance built with success over time at Kodak.

5.1 What could have saved Kodak’s Moment?

Kodak’s main competitor Fuji’s growth and survival in the digital age convinces us that Kodak could have prevented the Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection disaster. But Kodak’s problem lay in long-term problems like being stiff with its culture, inconsistent leadership and unsuccessful diversification that couldn’t have been changed in a few years’ time.

One solution that Kodak could have adopted to solve its innovator’s dilemma is – early around 1975, Kodak could have established a different startup for its digital imaging away from Rochester (Probably in the tech hub – Silicon Valley) and built a separate workforce for its digital technology.

Perhaps, an important question today is what innovative companies can learn from the disaster of an immensely successful and innovative company like Kodak?

Innovation in itself isn’t enough, being able to predict and adapt to change can be the key to sustainable business among others.